|

|

|

|

The Seznec Affair |

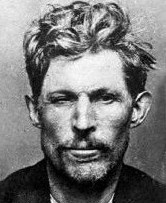

| Classification: Murderer? |

| Characteristics: The body was never found - Miscarriage of justice? - Symbolise the reluctance of French justice to admit the possibility of a mistake |

| Number of victims: 1 ? |

| Date of murders: May 25, 1923 |

| Date of arrest: June 14, 1923 |

| Date of birth: 1878 |

| Victim profile: Pierre Quéméneur, 46 (woodcutter and conseiller général of Finistère) |

| Method of murder: ??? |

| Location: France (during a business trip from Brittany to Paris) |

| Status: Sentenced to to hard labour in perpetuity on November 4, 1924. Released in May 1947. Died on February 13, 1954 |

|

The Seznec Affair was a controversial French court case of 1923-1924. Course Joseph Marie Guillaume Seznec, born in Plomodiern in Finistère in 1878 and the head of a sawmill at Morlaix, was found guilty of false promise and of the murder of the wood merchant Pierre Quéméneur, conseiller général of Finistère. Among other things, Quéméneur had strangely disappeared on the night of 25/26 May 1923 during a business trip from Brittany to Paris with Seznec, a trip linked (according to Seznec) to the sale of stocks of cars (left behind in France after the First World War by the American army) to the Soviet Union. Though many other possibilities were advanced as to the disappearance and despite the body never being recovered, it was decided only to pursue the murder hypothesis. Seznec became the prime suspect as the last person to have seen Quéméneur alive, and was arrested, charged and imprisoned. His 8-hour trial, in the course of which nearly 120 witnesses were heard, closed on 4 November 1924. Seznec was thus found culpable, but since premeditation could not be proved and so he was condemned to hard labour in perpetuity (the avocat général had demanded the death penalty). He was taken to the Transportation Camp at Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni in 1927, before being transferred to the prison of the Îles du Salut in French Guiana in 1928. Benefitting from a remission in his sentence in May 1947, he returned to Paris the following year. In 1953, in Paris, he was reversed into by a van that then drove off (the driver, later questioned, claimed not to have seen anything) and died of his injuries on 13 February 1954. Miscarriage of justice? Throughout the trial and for the rest of his life, Seznec never stopped proclaiming his innocence. His descendents fought on to have the case reopened and clear his name (notably his grandson Denis Le Her-Seznec). Until today, all their attempts (14 in total) have failed. The "commission de révision des condamnations pénales" nevertheless accepted, on 11 April 2005, a reopening of Guillaume Seznec's conviction for murder. This decision could open the way to an eventual annulling of his conviction in 1924. The criminal chamber of the Court of Cassation, France's appeals court, examined the case on 5 October 2006. At this point, Avocat général Jean-Yves Launay required the benefit of the doubt, to Seznec's benefit, raising more particularly the possibility of a police plot - the trainee inspector Pierre Bonny (twenty years later to be assistant to Henri Lafont, head of the Gestapo française) and his superior, commissaire Vidal were charged in the inquiry. At his side, the conseiller rapporteur Jean-Louis Castagnède maintained the opposite opinion, deducing on the one hand any such manipulation seemed improbable due to the few acts established by Bonny and on the other that the experts solicited by the cour de cassation had established that Guillaume Seznec really was the author of the false promise of sale of Quéméneur's property seized at Plourivo. On 14 December 2006, the Cour de révision refused to annul Seznec's conviction, judging there was no new evidence to call doubt on Seznec's guilt, since the implication of inspector Bonny is (though an interesting element in itself) not new. The affair seems closed and a new request for an annulment unlikely. The Seznec family at first intended to take the case to the European Court of Human Rights, but gave up on their lawyers' advice. In popular culture Several works have been published on the affair, and Yves Boisset directed the film L'Affaire Seznec in 1992, with Christophe Malavoy in the lead role and also starring Nathalie Roussel, Jean Yanne and Bernard Bloch. Bibliography

Wikipedia.org French murder verdict upheld - 82 years on Mystery lingers over killing with no corpse - Family fought for decades to try to clear man's name Angelique Chrisafis - The Guardian Friday 15 December 2006 It was one of the biggest French murder mysteries of the past 100 years: a killing with no corpse and a convicted murderer who always said he was innocent. Guillaume Seznec, a Breton sawmill owner, was sentenced to a life of hard labour in a penal colony in French Guiana in 1924 for murdering a dignitary and friend whose body was never found. He insisted he was innocent and over decades new theories have emerged of a curious saga of illegal rackets in American Cadillacs and a possible police set-up by a French officer who later joined the Gestapo during the Nazi occupation. The case inspired numerous books, while Seznec's family fought to force the courts to acknowledge a miscarriage of justice. But yesterday, amid intense interest from the media, lawyers and historians, the court of revision refused to posthumously clear Seznec's name. Last year the state prosecutor concluded that fresh evidence cast doubt on the guilty verdict. But judges insisted there were no new facts leading them to doubt Seznec's conviction. "It is shameful what you are doing!" shouted Seznec's grandson, Denis, 59, from the gallery, accusing the courts of wasting a chance to prove the justice system was able to admit its mistakes. The case comes as the legal system is reeling from the failures of a case in Outreau in northern France where several innocent people were jailed for years for paedophile offences, with some having their children taken into care. Some of those finally acquitted in that case were present in court with the Seznec family yesterday. In May 1923 Seznec left Brittany for a trip to Paris with a friend, Pierre Quemeneur, a woodcutter and local official. They were to negotiate with Boudjema Gherdi the sale of 100 Cadillac cars, left by US troops after the first world war. But their car broke down several times and Quemeneur decided to take the train alone. He never arrived in Paris and his body was never found. The following month his suitcase was found at Le Havre with a note in which Quemeneur promised to sell his land to Seznec. Seznec's family argue the document was faked. At Seznec's trial lawyers claimed that Gherdi did not exist, and that Seznec had planned Quemeneur's murder to take over his land. But Gherdi was later proved to exist. He was a car trader and an informer for a police officer on the case, inspector Pierre Bonny. The Seznec family questioned whether the police had framed Seznec to cover up a racket in American cars. In 1993 an 85-year-old former shopkeeper retracted statements implicating Seznec, saying she had been coerced by the police. Bonny joined the French Gestapo during the occupation and was shot by firing squad in January 1945. On the eve of his execution, his son Jacques said he confessed to having sent an innocent man to a penal colony. French justice willing to retry 1923 murder mystery By John Henley - Guardian,co.uk April 12, 2005 Judges in Paris yesterday cleared the way for the retrial of a murder mystery dating back 80 years which has come to symbolise the reluctance of French justice to admit the possibility of a mistake. "This is a historic day for our family," declared Denis Seznec, 58, grandson of a Breton sawmill owner sentenced to deportation and hard labour for life in 1924 for the murder of a local dignitary which he denied till the day he died. "After a campaign that has lasted three generations, this is the first time that the French justice system has finally decided to drop its illusion of infallibility," Mr Seznec added. The packed court erupted in cheers as the ruling was read. The case will go to France's highest court, the Cour de Cassation, to decide whether to grant the family's request - its 14th since 1926 - for the original verdict to be overturned. Guillaume Seznec left Brittany for Paris with his friend Pierre Quemeneur, a businessman and councillor, on May 25 1923. The pair were to negotiate with Boudjema Gherdi the sale of 100 Cadillac cars, left by US troops after the first world war. Their car broke down repeatedly, so, according to Seznec, his partner decided to carry on alone by train. Quemeneur never arrived in Paris, and his body was never found. Seznec was convicted of murder the following year. The prosecution argued that Gherdi was "a figment of the accused's imagination", and that Seznec did away with Quemeneur to get his hands on the latter's country estate: a fake bill of sale, dated May 23, was found among Seznec's belongings. He was deported in April 1927 to the infamous penal colony of French Guiana; it took nearly 20 years before he won a presidential pardon for good behaviour, and on his return he was a broken man. He died in 1954 at 75. Over the years, partly thanks to painstaking research by his grandson, it became apparent that Seznec could have been framed. Gherdi, it was discovered, did exist, apparently an informer for the investigating police officer, Inspector Pierre Bonny. Before the second world war came, Bonny was thrown out of the police for falsifying evidence; in the occupation, he joined the French Gestapo in Paris, where, after liberation, he was shot by firing squad in January 1945. Colette Noll, a resistance member deported on Bonny's orders, has testified that Gherdi informed on her and smashed her network, and the Algerian-born go-between was a "very frequent visitor" to the French Gestapo's HQ. Amid huge media interest, this year the Paris public prosecutor said he was "completely convinced" of Seznec's innocence. Yesterday's panel could not bring itself to go so far. It merely stated that Gherdi, and a connection between him and Bonny, were "new elements" which should be examined. Much of Bonny's case against Seznec remained valid, it added. "This case has ruined my life," a tearful Denis Seznec said outside court. "I don't regret it, but it has stopped me living. Now, for the first time, there may be light at the end of the tunnel". |